“Shared bikes are too heavy!”

Back in 2021, Jonathan Maus of BikePortland.org created a post ruminating about all the potential good things that could be done with the Social Bicycles 3.5 fleet operated by Biketown PDX (the fleet was since acquired by the amazing SoBi operator that is Hamilton Bike Share).

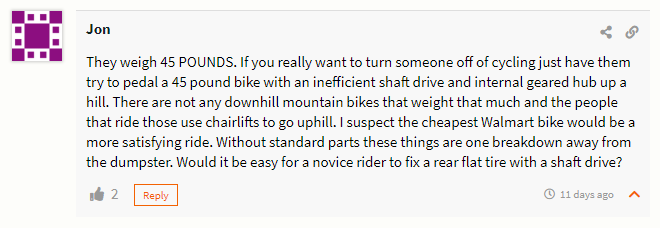

Then another unrelated Jon popped up in the comments – with something a little less productive to say:

While his argument about weight isn’t entirely unreasonable for areas with hilly terrain, comparing an 8-speed Nexus-equipped bike share bike with a Wal-Mart “bicycle shaped object” took an otherwise reasonable argument into the territory of trolling.

So just how “heavy” are shared bicycles?

Are they significantly heavier than comparable bikes from a bike shop?

How much of the weight is excess that would be shed as a personal bike?

How heavy are the framesets?

As most of us are probably aware, hybrids and casual MTBs often get turned into commuters, snow bikes, and wet weather beaters; these bikes aren’t exactly light. So are shared bikes really that much heavier, or are we being misled by the weight weenies?

We figured it was time for some empirical data for once and decided to compare some three dockless bikes – bikes that since have hit the used market: A Shanghai General ofo, a second-generation LimeBike, and Spin’s Chintone 3. They’re fairly representative of a retired bike share bike one might legally find for sale in 2024.

Each frame is designed for 26″/ISO 559 wheels and are made of aluminum of unknown metallurgy. Let’s put it this way: These ain’t 6061. The Lime and Spin also have steel forks, while the variation of ofo we’re using has an aluminum fork with a press-fit steel steerer tube. Headsets were left on the forks when weighed, though each share nearly identical headset parts, and their weight is negligible.

Since we’re not counting grams here, I measured all of these with simple digital scales from Amazon. Lightness is a virtue, but there’s a not-so-fine line to draw between a reliable errand bike and last year’s credit card tourer.

Keep in mind that we’re not willing to judge weight upon the merits of aluminum over steel and vise-versa. We understand lightweight steel bikes too (e.g., Reynolds 531/753/853 or Columbus SL/SLX/EL/OS) and don’t believe in equating frame material alone as an indicator of weight or quality.

I should also point out – though we have a few SoBi 3.0’s in the Museum, I wasn’t ready to tear one of them down for this test. All three of the frames here had already been partially disassembled due to fork or wheel damage, facilitating the test. The SoBi 3.0 also uses a shaft drive that’s partially integral to the frame, so weighing the 3.0 wouldn’t have been an exact comparison with the chain drive frames.

So, without further ado, let’s get into it.

Shanghai General Ofo

This beast is one of the three ofo designs to be deployed in the United States (the two-tone “bumblebee” ofos in the UK, while similar, are not the same frame). They’re fairly common, and brand new ones still continue to surface around the country at thrift shops and in bulk from third party sellers. Spare forks have also floated around on eBay at times, usually for around $20-25.

As a complete bike, the Shanghai General ofo weighs in at a hefty 42.59 lbs (19.32 kg).

As a frameset, it comes in at 5.62 lbs (2.55 kg), and – as I mentioned above – it is the only one of the three to have an aluminum fork with a press-fit steel steerer. The fork comes in at 2.2 lbs (0.998 kg).

LimeBike V2

If you’ve ever picked up any of the bikes in this comparison, it’s easy to assume the LimeBike is the heaviest, weighing in at about 46.12 lbs (20.92 kg) when built – without the Li-Po battery inside it (more on that in a minute).

As a complete bike, you’d be right. But not as a frameset.

The Lime-B v2 – an update upon the original, aluminum-wheeled Lime-B – is heavier than the others for a few reasons. In addition to the usual penalty of solid tires, hidden in the downtube is a 1.2 pound (0.54 kg), 3.7V 20Ah Li-Po battery, put there to give the lock ample power – even if the solar charger was out of the sun’s reach for an extended period of time.

In fact, this is why Lime chose to cut the headtube off many of their bikes – to dispose of the Li-Po quickly. Also adding to the weight is the front basket on the Limes – larger than the others, made from wire steel, and supported by a U-shaped stay running from under the basket to the front axle.

The frame we weighed, unfortunately, had been vandalized at one point. When it was handed to us by the local Parks department, the entire lock plate had been ripped off at its welds. As such, the weight below may be ever so slightly less than a proper Lime-B frameset.

That said, this particular Lime-B V2 frame edged out the ofo just slightly at 5.52lbs.

However, all the beef is in the Lime’s fork, which weighs a whopping 3.52lbs. It’s also the only fork here with a 110mm OLN width (Note: Tianjin Fuji-Ta ofos are also spaced at 110mm).

Spin Chintone 3

The Spin Chintone 3 is one of the last incarnations of Spin’s pedal-only bike share equipment before they went electric with the Segway Ninebot A200 (“S-100″/”A80″) and later with the X100/A300/S80 and Okai equipment. These were also their first pedal bike to run on 26″ wheels as opposed to 26 x 1-3/8” wheels.

The Chintone 3’s are arguably Spin’s most robust, non-electric model, and nearly 500 of them comprised the big Spin Bike Donation Project we did back in 2019.

The Spin is the lightest of the three as a complete bike, coming in at a respectable – but reasonable – 40.17 lbs (18.22 kg).

When reduced to a frameset, the Spin Chintone 3 and the Lime-B v2 are not too different; some details are shared with ofos too. Just like many commercially-available bike shop hybrids, the similarities are numerous when you look at them closely with their peers. Likewise, their frameset weights aren’t that different, though the Chintone 3 edges out the other two at 5.18lbs; the lightest frame of the three.

The ofo still has the upper hand as far as fork weight though. The Spin’s fork comes in just a bit heavier at 2.54lbs.

For giggles: Social Bicycles 5.5

Adding a purpose-built e-bike into the mix isn’t a fair comparison, but we happened to have a SoBi 5.5 disassembled to the frameset (and being completely polished – as a friend of the museum put it, it’s “a bike trying to be an American Airlines MD-80”), so the opportunity was too good to pass up.

The frameset alone – sans fork – came out to 12.56 lbs (5.7 kg). If you’ve ever ridden the original 4.5 model – the “e-bike ready” version of the 5.0 minus the battery – then you know how heavy these are. But again, throwing in a purpose-built e-bike into the mix isn’t exactly fair or consistent with this exploration of analog pedal bikes (or “pushbikes,” if you prefer).

First thoughts:

The weight of the forks was more surprising than the frames. The frames need to be pretty beefy to put up with the abuse and vandalism of the general public, but these bikes were clearly engineered to take a few hits from riders crashing straight into solid brick walls. Considering that decent hi-ten road forks from the 1980’s run about 30 ounces (or 1.875 pounds), these forks are impressively heavy and the Lime fork borders on absurdity. Yet, weight is no guarantee of strength, as we’ve come across two bent Chintone 3 forks.

But these aren’t road bikes, nor is it fair to compare these weights against the best of lightweight steel frames and carbon fiber forks. Rather, let’s ask another question:

How do personal bikes compare?

Stow-A-Bike V2 MTB

From the department of bicycle shaped objects comes this embarrassing thing. It’s a poster child for horrible, Wal-Mart-level dual-suspension mountain bikes, complete with a five pound, solid steel crankset that helps to make the built frame – sans wheels, handlebar, or saddle – weigh an outrageous 19.96 pounds (9.05 kg).

It’s also an excellent example of the type of department store bicycle that Comments Area Jon claims is “more satisfying” for an average rider.

So what does it weigh when stripped to a bare frame (with spring) and fork? A colossal 10.04 lbs (4.56 kg) for the frame and 4.3 lbs (1.95 kg) for the fork. The only frameset heavier in this comparison is the Social Bicycles 5.5, which – as we mentioned before – is a purpose-built electric share bicycle which sits somewhere between bicycle and moped.

I couldn’t be bothered to get a built weight on the Stow-An-Anchor, but the manufacturer claims 36 lbs (16.32 kg). The single-wall rims that came with it felt light enough that this is probably accurate.

2016 Specialized Expedition

One of these misshapen Specialized hybrids made its way to me for repair once, so I had an opportunity to weigh it. While I couldn’t tear it down to the frame, I was able to weigh it as-is, minus saddle. 31.4 lbs (14.243 kg).

2012 Schwinn Voyageur R21

Another comfort hybrid that was opportune to weigh, equally misshapen as the Specialized, and complete with saddle. 32.28 lbs (14.64 kg).

1952 Raleigh Sports

For contrast – and some retrogrouch giggles – I couldn’t resist weighing this 1952 Raleigh Sports which I’m currently refurbishing. Raleigh city bicycles made prior to the company’s mid-1960’s takeover by Tube Investments (TI) are known for being extremely strong and a touch heavier than their 1970’s counterparts.

So how different is the weight of a 3-speed of 70 years ago to the dockless 3-speed of today or the folding Stow-An-Anchor abomination?

With the drive side bottom bracket cup and headset still partially installed, the frame of the early Sports weighs in at 6.4 lbs (2.9 kg). Its high-tensile fork – 1.98 lbs (0.9 kg).

Of course, when it comes to outright cool factor, it’s hard to beat a jet black, full-chaincase Sports that looks like it just rolled out of Mary Poppins Returns (“Gertie” was a Pashley Roadster built with a low top tube) – but that’s another story.

The leaderboard:

Shared bikes:

| Model/Provider | Assembled weight | Frame weight | Fork weight |

| ofo (Shanghai General) | 42.59 lbs | 5.62 lbs | 2.20 lbs |

| Lime-B | 46.12 lbs | 5.52 lbs | 3.52 lbs |

| Spin Chintone 3 | 40.17 lbs | 5.18 lbs | 2.54 lbs |

| Social Bicycles 5.5 (e-bike) | N/A | 12.56 lbs | 5.08 lbs |

Personal bikes:

| Model | Assembled weight | Frame weight | Fork weight |

| Stow-A-Bike V2 26″ | 36 lbs (claimed) | 10.04 lbs | 4.30 lbs |

| 2016 Specialized Expedition | 31.4lbs | N/A | N/A |

| 2012 Schwinn Voyageur R21 | 32.3 lbs | N/A | N/A |

| 1952 Raleigh Sports | 42 lbs | 6.40 lbs | 1.98 lbs |

So, is share bike weight another misconception?

If a bike share bike is supposedly “garbage” by virtue of the weights we’ve seen above, this logic would dictate that the great majority of hybrid comfort bikes and casual mountain bikes sold by bike shops for the last 20 years fall into the same category along with the bicycle-shaped-objects from Wal-Mart.

Not really a fair assessment, is it?

Regardless, retired dockless bikes usually fall into the genre of short distance commuting bikes/shoppers where lightness becomes an exercise in futility the moment the bike is fully loaded for the ride home. Any argument in favor of a flexy, lively frame flies out the window and into the next county if the same frame oscillates uncontrollably when weighed down. If the ride quality feels a bit dead, tough – it’s still better than a trip in…an SUV.

Still, a bike shouldn’t be any heavier than it must be, and all of these dockless bikes do present a number of weight-saving opportunities.

Simply swapping to pneumatic tires offers a fair amount of weight savings. The solid Drogen tires used on Spin Chintone 3s are 1.54 lbs each (0.7 kg), while the Wanda (WD)’s fitted on ofos and Lime-B’s are an eyebrow-raising 3.42 lbs each (1.55 kg/ea), meaning that 6.84 pounds of a Lime-B V2 are in the solid tires alone.

There’s nothing special about the rims on these bikes, so if you pry off the solid tires, you’ll find normal, hooked-bead aluminum rims. All one has to do is drill a valve hole out and mount conventional 26×1.5 tires, tubes, and tire liners on them to shed this excess weight and improve the ride immensely.

Speaking of which, changing the tire on a shaft-drive SoBi 3.0 – the model previously used by Biketown PDX – or similar is not difficult at all; in fact, it might be easier for most novices to pull a wheel on a shaft drive bike and be guaranteed to re-seat the wheel correctly upon installation. The only thing that makes it difficult on a SoBi is tire-to-fender clearance; fender stays usually have to be loosened, though this is standard operating procedure for just about any shared bike with a full rear fender.

But weight, past the removal of any obvious excess, is arguably not even the primary concern I’d have about dailying an ex-share bike.

If anything, brake and bearing adjustment, plus tire inflation are much more critical to a satisfactory ride. Case in point, the Kuarasara front band brakes fitted to the Limes and ofos (the rears are drums, even if they look like band brakes) are rarely adjusted well, and usually drag. When band brakes drag – even a tiny bit – they can turn a simple ride into something absolutely exhausting. By comparison, the Sturmey front drum brake and Shimano rear roller brakes on Spin Chintone 3s present very little resistance, enough that these very similar bikes can be night-and-day experiences to ride. Note: For the record, I’ve found that band brakes respond exceptionally well when they’re actuated by linear-pull brake levers, and the extra cable pull allows them to be adjusted quite slack. They have to be set fairly slack as they tend to lock too easily otherwise.

I’ve also thrown a Spin fork and front wheel on a Lime frame. It turned a frustrating bike into something a lot more tolerable (keep in mind that the steerer tube lengths required significant chopping of the Lime’s headtube).

If there was ever dramatic proof that rolling resistance is arguably more important than weight, our Social Bicycles 5.5’s are all the proof anyone could ask for. With factory Kenda 26×1.95″ tires at 65psi, a friction free disc brake up front, and a Sturmey-Archer 90mm drum in back, these e-bike (minus battery) behemoths with their 12 pound frames roll more comfortably than a stock ofos or Lime-B with slightly dragging band brakes. True, you’ll probably be rolling slower, but they’re comfortably heavy, not tiresome.

Put simply, for the average person looking for a simple commuter bicycle that gets from A-to-B that they don’t have to fuss over – especially if one doesn’t have the funds to splurge on something nice – a retired share bike is just fine as-is.

Take that, “Jon.”